This is a tale of a marine and an orphan, born over 5000 miles from each other, who find each other because of what they have lost.

This is a tale of a marine and an orphan, born over 5000 miles from each other, who find each other because of what they have lost.

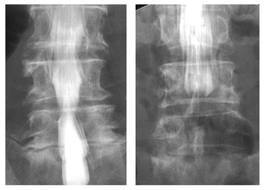

Oksana Alexandrovna Boudarchuk is born in Khmelnitsky, Ukraine on June 19, 1989 with 6 toes, 5 webbed fingers on each hand, and no thumbs, a condition called “tibial hemimelia.” Her leftleg is 6 inches shorter than the other and both legs are missing weight-bearing bones. Her parents go “missing in action” and she begins a lonely and catastrophic journey through revolving orphanages where she is beaten and raped with regularity.

Rob Jones grows up on a 200-acre farm in Lovettsville, Virginia where his small stature brings alarm to his parents. After his doctor’s clearance to play sports, he does so until the 10th grade when he decides to escape into the world of computer games and entertains the possibility of becoming a video-game developer.

A single woman and speech pathology professor, Gay Master from Buffalo, New York, begins her search for a newborn baby to adopt, until someone shows her a picture of Oksana and she declares, “That’s my child.” Only after persevering the 2-year ban on Ukrainian adoptions does her dream come true. A late night in January of 1997, Gay finds Oksana wrapped in a sweater in a freezing building. When she wakes up she says in Ukrainian, “I know who you are. You’re my mother. I have a picture.”

Fast-forward to Rob’s junior year at Virginia Tech University and you find him making the decision that will change his life forever. He signs up for the Marines with no real clear reason: “I realized that there are things out there that are more important than me.” Despite no strong political or moral reasons, “or even the ‘why’ of his country’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; he just wanted to live through the what of them.”

Oksana and Gay move to Louisville, Kentucky in 2001 and it feels like an avalanche of change for the budding teenager. A surgery to remove the leg above the knee followed by therapy and prosthetic legs stretch the boundaries for this painfully self-aware 12-year old. At age 13 and before her second amputation, she learns the “privacy” of rowing. As she attacked the water, “the central theme of her early life was inverted. She could be as violent as she wanted, while everything around her stayed serene.”

Rob enlists in January of 2008 and goes to Iraq as a lance corporal specializing in IED (improvised explosive device) detection. His tour of duty ends in August of that same year, but in April of 2010 he is deployed to Afghanistan. One day in July while clearing the area after a blasting cap explodes, an IED blows his legs off. In his shock and disorientation, he asks a fellow marine to kill him. After a morphine injection, he flies to his base and then Germany before finally landing back in the states at Bethesda Naval Hospital 3 days later. By then, he has changed his mind about ending his life.

I discover what brings this marine and orphan together when I read their amazing story in a Sports Illustrated article by Michael Rosenbergat the end of August. They are training for the Paralympics in London in the mixed double sculls, where I later discover they win a bronze medal, the first U.S. medal ever in this event.

What brings them together is their loss … their loss of limbs and heightened awareness of life’s fragile nature. Both remember moments of life ending and then suddenly beginning again.

What brings them together is their pain … the pain of their past and the ongoing “phantom” pain of their present. Both speak to the moments when bursts of pain come to the legs they no longer have.

What now sends them on their way is the belief that they will not waste a single day of their life. And neither should you!